UFR 3-35 Test Case: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 105: | Line 105: | ||

= CFD Code and Methods = | = CFD Code and Methods = | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

We applied our in-house finite-volume code MGLET with a staggered Cartesian grid. The grid was equidistant in the horizontal directions and stretched away from the wall in the vertical direction by a factor smaller than <math>1.01</math>. The horizontal grid spacing was four times as large as the vertical one. The time integration was done by applying a third order Runge-Kutta sheme, the spatial approximation by second order central differences and the maximum of the CFL number was in the range of 0.55 to 0.82. To model the cylindrical body, a second order immersed boundary method was applied (Peller et al.2006; Peller 2010). The sub-grid scales were modelled using the Wall-Adapting Local Eddy-Viscosity (WALE) model (Nicoud & Ducros 1999). Around the cylinder, the grid was refined by three locally embedded grids (Manhart 2004), each reducing the grid spacing by a factor of two (see Fig. 4). A grid study by Schanderl & Manhart 2016 shows that the number of grid refinements was sufficient. The resulting grid spacing in the vertical direction at the bottom plate around the cylinder was smaller than approximately 1. | We applied our in-house finite-volume code MGLET with a staggered Cartesian grid. The grid was equidistant in the horizontal directions and stretched away from the wall in the vertical direction by a factor smaller than <math>1.01</math>. The horizontal grid spacing was four times as large as the vertical one. The time integration was done by applying a third order Runge-Kutta sheme, the spatial approximation by second order central differences and the maximum of the CFL number was in the range of 0.55 to 0.82. To model the cylindrical body, a second order immersed boundary method was applied (Peller et al.2006; Peller 2010). The sub-grid scales were modelled using the Wall-Adapting Local Eddy-Viscosity (WALE) model (Nicoud & Ducros 1999). Around the cylinder, the grid was refined by three locally embedded grids (Manhart 2004), each reducing the grid spacing by a factor of two (see Fig. 4). A grid study by Schanderl & Manhart 2016 shows that the number of grid refinements was sufficient. The resulting grid spacing in the vertical direction at the bottom plate around the cylinder was smaller than approximately 1.9 wall units (based on the wall-shear stress of the approaching flow in the Precursor, averaged over the span <math> -1.25 < y/D < 1.25</math>) (Schanderl & Manhart 2016). The fraction of the modelled dissipation is about 30% of the total dissipation rate (Schanderl & Manhart 2018). | ||

The setup simulated was intended to be identical to the experimental one. To model the bottom and side walls, we applied no-slip boundary conditions, whereas the free surface was modelled by a slip boundary condition. Therefore, the Froude number in the LES was infinitesimal and no surface waves occurred. By conducting a precursor simulation a fully-developed turbulent open-channel flow was achieved as inflow condition. The streamwise boundary conditions were periodic, and the precursor domain had a length of 30D (see Fig. 4). The wall-nearest point of the precursor grid had a distance of 7.5 wall units. | The setup simulated was intended to be identical to the experimental one. To model the bottom and side walls, we applied no-slip boundary conditions, whereas the free surface was modelled by a slip boundary condition. Therefore, the Froude number in the LES was infinitesimal and no surface waves occurred. By conducting a precursor simulation a fully-developed turbulent open-channel flow was achieved as inflow condition. The streamwise boundary conditions were periodic, and the precursor domain had a length of 30D (see Fig. 4). The wall-nearest point of the precursor grid had a distance of 7.5 wall units. | ||

| Line 113: | Line 113: | ||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align: center;" border="1" style="margin: auto;" | {| class="wikitable" style="text-align: center;" border="1" style="margin: auto;" | ||

|+ style="caption-side:bottom;"|Tab. 3: Applied grids in the LES | |+ style="caption-side:bottom;"|Tab. 3: Applied grids in the LES (Schanderl & Manhart 2016) | ||

! Grid | ! Grid | ||

! Level of refinement | ! Level of refinement | ||

| Line 151: | Line 151: | ||

| 3 | | 3 | ||

| <math>250/1000</math> | | <math>250/1000</math> | ||

| <math>7.5/7.5/1. | | <math>7.5/7.5/1.9</math> | ||

| <math>177\cdot 10^6 </math> | | <math>177\cdot 10^6 </math> | ||

|} | |} | ||

Revision as of 14:16, 17 January 2020

Cylinder-wall junction flow

General Remark

The experimental and numerical setups applied in this study were described in detail by Schanderl et al. (2017b) (PIV and LES). The experiment is further described by Jenssen (2019), the numerics in Schanderl & Manhart (2016), Schanderl et al. (2017a) and Schanderl & Manhart (2018). Thus, the following shall provide a brief overview only.

Test Case Experiments

In order to provide both numerical and experimental data acquired for the same flow configuration under identical (as good as possible) boundary conditions, we performed a large eddy simulation and a particle image velocimetry experiment. We studied the flow around a wall-mounted slender () circular cylinder with a flow depth of . The width of the rectangular channel was (see Fig. 1). The investigated Reynolds number was approximately , the Froude number was in the subcritical region. As inflow condition we applied a fully-developed open-channel flow.

Experimental set-up

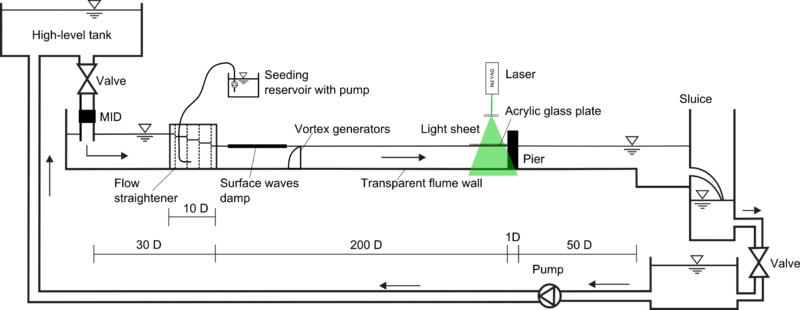

The experimental set-up is shown in Fig. 2. A high-level water tank fed the flume with a constant energy head. After the inlet, a flow straightener, a surface waves damper and vortex generators as recommended by (Counihan 1969) were installed such that the turbulent open-channel flow developed along the entry length of . A sluice gate at the end of the flume controlled the water depth before the water recirculated driven by a pump. The experimental parameters are listed in Table 1:

| Description | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Cylinder diameter | ||

| Flow depth | ||

| Channel width | ||

| Flow rate | ||

| Depth-averaged velocity of approach flow | ||

| Kinematic viscosity | ||

| Reynolds number | ||

| Reynolds number | ||

| Reynolds number |

Measurement technique

The experimental data were acquired by conducting planar monoscopic 2D-2C PIV in the vertical symmetry plane upstream of the cylinder. The PIV snapshots were evaluated by the standard interrogation window based cross-correlation of . Doing so, we achieved instantaneous velocity fields of the streamwise () and the wall-normal () velocity component. From these data the time-averaged turbulent statistics were calculated in the post-processing. We used a CCD-camera with a square sensor. The size of a pixel was , therefore the spatial resolution of the images was . The size of the interrogation windows was . The temporal resolution was , which is approximately twice the macro time scale . The light sheet was approximately 2mm thick provided by a Nd:YAG laser. The f-number and the focal length of the lens were and , respectively.

At the measurement section, the flume had transparent walls. Therefore, the laser light, which entered the flow from above could pass with a minimum amount of surface reflections through the bottom wall. However, an acrylic glass plate had to be mounted at the water-air interface to suppress the bow waves of the cylinder and let the light sheet enter the water body perpendicularly (see Fig. 3). The influence of this device at the water surface was tested and considered to be insignificant at the cylinder-wall junction.

Hollow glass spheres were used as seeding and had a diameter of . The corresponding Stokes number was , and therefore, the particles were considered to follow the flow precisely.

The total number of time-steps was , the time-delay between two image frames of a time-step was . Therefore, the total sampling time was or . During the experiment seeding and other particles accumulated along the bottom plate, which undermined the image quality by increasing the surface reflection. Therefore, the data acquisition was stopped after images to allow surface cleaning and to empty the limited capacity of the laboratory PC's RAM. The sampling time of such a batch was or .

The data acquisition time and number of valid vectors was validated by the convergence of statistical moments. In the centre of the HV the number valid samples had its minimum. Therefore, the time-series at the centre of the HV was analysed as a reference for the entire flow field. The standard error of the mean was times the standard deviation, the corresponding error in the fourth central moment is .

The PIV set-up is shown in detail in Fig. 3, including the qualitative size of the field-of-views (FOV) for investigating the approaching boundary layer as well as the flow in front of the wall-mounted cylinder.

The standard error of the mean value of the measured velocities was determined as follows:

,

the standard error of the higher central moments was obtained likewise:

.

The standard errors with respect to the standard deviation were quantified as follows:

CFD Code and Methods

We applied our in-house finite-volume code MGLET with a staggered Cartesian grid. The grid was equidistant in the horizontal directions and stretched away from the wall in the vertical direction by a factor smaller than . The horizontal grid spacing was four times as large as the vertical one. The time integration was done by applying a third order Runge-Kutta sheme, the spatial approximation by second order central differences and the maximum of the CFL number was in the range of 0.55 to 0.82. To model the cylindrical body, a second order immersed boundary method was applied (Peller et al.2006; Peller 2010). The sub-grid scales were modelled using the Wall-Adapting Local Eddy-Viscosity (WALE) model (Nicoud & Ducros 1999). Around the cylinder, the grid was refined by three locally embedded grids (Manhart 2004), each reducing the grid spacing by a factor of two (see Fig. 4). A grid study by Schanderl & Manhart 2016 shows that the number of grid refinements was sufficient. The resulting grid spacing in the vertical direction at the bottom plate around the cylinder was smaller than approximately 1.9 wall units (based on the wall-shear stress of the approaching flow in the Precursor, averaged over the span ) (Schanderl & Manhart 2016). The fraction of the modelled dissipation is about 30% of the total dissipation rate (Schanderl & Manhart 2018).

The setup simulated was intended to be identical to the experimental one. To model the bottom and side walls, we applied no-slip boundary conditions, whereas the free surface was modelled by a slip boundary condition. Therefore, the Froude number in the LES was infinitesimal and no surface waves occurred. By conducting a precursor simulation a fully-developed turbulent open-channel flow was achieved as inflow condition. The streamwise boundary conditions were periodic, and the precursor domain had a length of 30D (see Fig. 4). The wall-nearest point of the precursor grid had a distance of 7.5 wall units.

| Grid | Level of refinement | Cells per diameter

horizontal / vertical |

Grid spacing

|

Number of grid cells |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precursor | 0 | |||

| Base | 0 | |||

| Grid 1 | 1 | |||

| Grid 2 | 2 | |||

| Grid 3 | 3 |

Inflow condition

Figure 5 shows the vertical time-averaged profiles along of the

- streamwise velocity

- Reynolds normal stresses

- Reynolds normal stresses

- Reynolds shear stresses

For comparison, the data of Bruns et al. (1992) are included at a comparable Reynolds number based on the momentum thickness .

The corresponding datasets can be downloaded from below. The first 11 lines belong to the header and are indicated by the #-symbol. For both PIV and LES, each column refers to the data listed in Table 3 and is comma separated. For MatLab users, we provide a script at the end of the section Evaluation of this document as an example of reading the data, which can be used as a template to modify for reading the inflow data as well.

| Column number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| PIV/LES |

- PIV data: Media:UFR3-35_X_inflow_data.txt

- LES data: Media:UFR3-35_C_inflow_data.txt

Contributed by: Ulrich Jenssen, Wolfgang Schanderl, Michael Manhart — Technical University Munich

© copyright ERCOFTAC 2019

![{\displaystyle [\mathrm {m} ]}](https://en.wikipedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/acc4ae614478b637a860b092f28574274341dd9d)

![{\displaystyle [\mathrm {m} ^{3}\mathrm {s} ^{-1}]}](https://en.wikipedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2ad47afa82c8fa83b5fe46c0225067900c72f2bf)

![{\displaystyle [\mathrm {m} \,\mathrm {s} ^{-1}]}](https://en.wikipedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/35037e6369e559b7be9f809ef8ea60ac6f4e3150)

![{\displaystyle [\mathrm {m} ^{2}\mathrm {s} ^{-1}]}](https://en.wikipedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/98a01648a230018ac0463ec2fc154aa6ea45c2de)

![{\displaystyle [-]}](https://en.wikipedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/25fa02b41c948a16ec1010ba03c183ef6a16f44c)