CFD Simulations AC2-08: Difference between revisions

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

|- | |- | ||

! scope="row" | LES | ! scope="row" | LES | ||

| FASTEST / Hahn et al.<ref name='hahn_investigation_2008'> </ref>, FASTEST / Kuenne et al.<ref name='kuenne_les_2011'>G. Kuenne, A. Ketelheun, J. Janicka, Combustion | | FASTEST / Hahn et al.<ref name='hahn_investigation_2008'> </ref>, FASTEST / Kuenne et al.<ref name='kuenne_les_2011'>G. Kuenne, A. Ketelheun, J. Janicka, Combustion Flame (2011), doi:10.1016/j.combustflame.2011.01.005.</ref> | ||

| FASTEST / Kuenne et al.<ref name='kuenne_les_2011'> </ref> | | FASTEST / Kuenne et al.<ref name='kuenne_les_2011'> </ref> | ||

Revision as of 21:14, 19 February 2011

Premixed Methane-Air Swirl Burner (TECFLAM)

Application Challenge 2-08 © copyright ERCOFTAC 2011

Introduction

The Tecflam configuration has been investigated by means of RANS (Reynolds Averaged Navier Stokes) and LES (Large Eddy Simulation). An overview will be presented in this section. Some details of the simulation program and the employed turbulence and combustion model will be given. In order to avoid an overload of information the interested reader is referred to the cited references for a detailed discussion.

Overview of Simulations

Since measurements of temperature and species mass fractions exist only for the 30 kW configuration only this case has been investigated by means of numerical simulations. The studies are summarized in table 4.1.

| Isothermal (30iso), CFD-Code / Publication | Reacting (PSF-30), CFD-Code / Publication | |

|---|---|---|

| RANS | FASTEST / Hahn et al.[1] | Ansys CFX / Kuenne et al.[2] |

| LES | FASTEST / Hahn et al.[1], FASTEST / Kuenne et al.[2] | FASTEST / Kuenne et al.[2] |

CFD Code

The Academic Solver FASTEST

The three-dimensional finite volume code FASTEST uses block-structured, hexahedral, boundary fitted grids to represent complex geometries. Regarding the velocity, spatial discretization is based on multi-dimensional Taylor series expansion[3] to ensure second order accuracy on arbitrary grids. To assure boundedness of scalar quantities the TVD-limiter suggested by Zhou et al.[4] is used. Within LES an explicit Runge-Kutta scheme is used for the time advancement of momentum and species mass fractions with temperature dependent transport coefficients. The code solves the incompressible, variable density, Navier-Stokes equations where an equation for the pressure correction is solved within each Runge-Kutta stage to satisfy continuity. The solver is based on an ILU matrix decomposition and uses the strongly implicit procedure[5] to take advantage of the block-structure.

The Commercial Solver ANSYS CFX

ANSYS CFX employs a conservative finite-element-based control volume method to solve the Navier-Stokes equations. The code supports unstructured meshes and the resulting system of equations is solved by a pressure-based algorithm. Since an extensive documentation exists for CFX a detailed description is omitted here.

Computational Domain, Spatial Discretization and Boundary Conditions

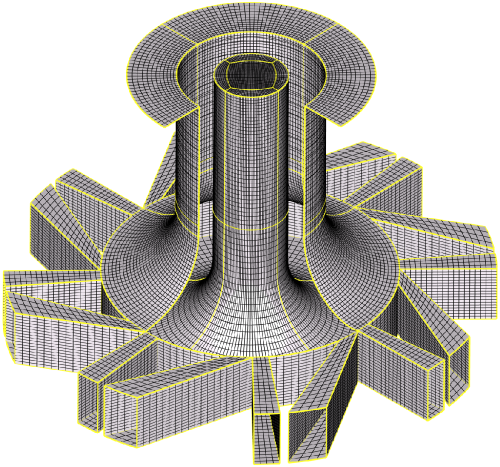

As illustrated in Fig. 4.1 and 4.2 the computational domain starts after the plenum chamber at the inlets of the tangential and radial channels. Here the mass flow given by the measurements has been set. No additional velocity fluctuation is forced here since the inclusion of the geometry upstream of the nozzle exit has been found to be sufficient to allow the turbulent structures to form. The equivalence ratio has been set to ϕ = 0.83 at the inlet since the methane-air mixture has been verified by the measurements to be mixed homogeneously. The diameter of the computational domain matches the extend of the coflowing air issuing with 0.5m/s. The boundaries in radial and axial direction have been found to be sufficiently far away from the region of interest (i.e. the swirler exit region). The block structured grid contains 3.2 million control volumes and has been elliptically smoothed to obtain a better orthogonality. The grid has been refined towards the near nozzle region whereas it gets coarser with increasing distance to spare cells.

Physical Modeling

RANS Closure

Within RANS the Reynolds stress tensor is modeled according to the standard k-ε model by Jones and Launder[6] , following a Boussinesq approximation where the turbulent viscosity is expressed dependent on the turbulent kinetic energy (k) and the dissipation rate (ε). FASTEST uses a flux blending to combine 1st order upwind with the 2nd order central differencing scheme. Within CFX the high resolution scheme has been used which combines 1st and 2nd order discretization along the border of stability.

LES Closure

Within the LES carried out with FASTEST the sub grid fluxes of momentum are accounted for by the eddy viscosity approach proposed by Smagorinsky[7] where the model coefficient is obtained by the dynamic procedure of Germano et al.[8] with a modification by Lilly[9]. Outside of the reaction zone a gradient approach has been chosen for the sub grid flux of scalar quantities with a turbulent Schmidt number of 0.7.

Combustion Modeling

For the RANS simulations done with ANSYS CFX the implemented Turbulent Flame Speed Closure (TFC) model has been used. It is based on an transport equation for the reaction progress and the mixture fraction to account for the chemical reaction and mixing with the coflowing air respectively. To close the chemical source term the correlation to express the turbulent flame speed in terms of turbulent scales developed by Zimont[10] has been used and the sensitivity related to its model coefficient has been investigated (see the Evaluation section).

Within the LES simulations done with FASTES combustion is described by means of tabulated chemistry coupled with the thickened flame approach[11][12][13][14][15]. The method introduced very recently[2] uses a two-dimensional table to describe the physical situation of mixing and chemical reaction within the burner. As suggested in the framework of FGM (flamelet generated manifolds)[16][17], the table generation is based on the simulation of one-dimensional freely propagating premixed flames using the detailed chemistry code Chem1D[18] which are repeated for different equivalence ratios to span a two-dimensional manifold that are parameterized by the mixture fraction and the CO2 mass fraction as progress variable as shown in Fig. 4.3. Details about the method and its verification can be found in Kuenne et al.[2].

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 F. Hahn, C. Olbricht, C. Klewer, G. Kuenne, R. Ohnutek, J. Janicka, in: Proc. of the ISTP19 (2008d).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 G. Kuenne, A. Ketelheun, J. Janicka, Combustion Flame (2011), doi:10.1016/j.combustflame.2011.01.005.

- ↑ T. Lehnhaeuser, M. Schaefer, International Journal for Numerical Methods in Fluids 38 (2002) 625–645.

- ↑ G. Zhou, L. Davidson, E. Olsson, in: Fourteenth International Conference on Numerical Methods in Fluid Dynamics, 1995, pp. 372–378.

- ↑ H.L. Stone, SIAM Journal on Numerical Analysis 5 (1968) 530–558.

- ↑ W. Jones, B. Launder, International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 15 (1972) 301–314.

- ↑ J. Smagorinsky, Monthly Weather Rev. 91 (1963) 99–164

- ↑ M. Germano, U. Piomelli, P. Moin, W.H. Cabot, Physics of Fluids A: Fluid Dynamics 3 (1991) 1760–1765.

- ↑ D.K. Lilly, Physics of Fluids A: Fluid Dynamics 4 (1992) 633–635.

- ↑ V. L. Zimont, Zimont, V. L., 1979. “Theory of Turbulent Combustion of a Homogeneous Fuel Mixture at high Reynolds Numbers”. Translated from Fizika Goreniya i Vzryva, 15(3) (1979), pp. 23–32.

- ↑ T. Butler, P. O’Rourke, Symposium (International) on Combustion 16 (1977) 1503–1515.

- ↑ P.J. O’Rourke, F.V. Bracco, Journal of Computational Physics 33 (1979) 185–203.

- ↑ C. Angelberger, D. Veynante, F. Egolfopoulos, T. Poinsot, in: Proceedings of the Summer Program 1998, Center for Turbulence Research, pp. 61–82.

- ↑ O. Colin, F. Ducros, D. Veynante, T. Poinsot, Physics of Fluids 12 (2000) 1843–1863.

- ↑ F. Charlette, C. Meneveau, D. Veynante, Combustion and Flame 131 (2002) 159–180.

- ↑ J.A. van Oijen, L.P.H. de Goey, Combustion Science and Technology 161 (2000) 113–137.

- ↑ J.A. van Oijen, F.A. Lammers, L.P.H. de Goey, Combustion and Flame 127 (2001) 2124–2134.

- ↑ Chem1D, A one-dimensional laminar flame code, developed at Eindhoven University of Technology, www.combustion.tue.n1/chem1d.

Contributors: Guido Kuenne (EKT), Andreas Dreizler (RSM), Johannes Janicka (EKT)

EKT: Institute of Energy and Power Plant Technology, Darmstadt University of Technology

RSM: Institute Reactive Flows and Diagnostics, Center of Smart Interfaces, Darmstadt University of Technology